Form letters that actually inform

The dreaded government letter. They are usually full of legal jargon, poorly laid out, and confirm all of our worst opinions about government. Worse, they don’t work. As Matt Darling’s article What can be learned from states that made good faith efforts with work requirements? (on the Substack Can We Still Govern) points out, too many of them bury the most important information at the end of a wall of words that deters all but the most determined.

At the Center for Civic Design, we’ve learned a lot about government letters from working with elections offices. We’ve focused on a subset of these letters that include a form component that the recipient can use to fix an issue or provide more information. They are used to let voters know when they are registered through a Motor Voter transaction, help them correct mistakes on other forms, or fix their absentee ballot envelope form so their ballot can be counted.

A big cheer went up in our office when we read the recommendation to design and user test letters that “effectively grab the reader’s attention and communicate the actions they need to take.” Doing that well requires skill in plain language, information design, and carefully planned nudges. It also requires changing the tone from a legal notice to a conversation that invites participation.

We start designing a form letter with 4 principles:

- Make it trustworthy. Help the recipients identify the office it came from with a few universally recognizable elements: the name of the office, contact information, and (as participants in our user testing told us over and over) “The form should have a seal on it to make it look official.”

- Explain the problem clearly. Write in plain language. Avoid (or explain) jargon. Write directly to the reader in active, positive sentences that tell them what they need to know and what they have to do.

- Be specific about the problem. Tell each person why they are getting this letter and show them what information it’s based on. Create separate letters for different problems, so everyone gets the details they need.

- Tell them how to take action successfully. If they have to return a form, tell them why and how. If there is an online version or more information on the web, give them a link (and a QR code for a web page). Make the requirements clear: Do they have to sign the form? Is there other required information? What is the deadline?

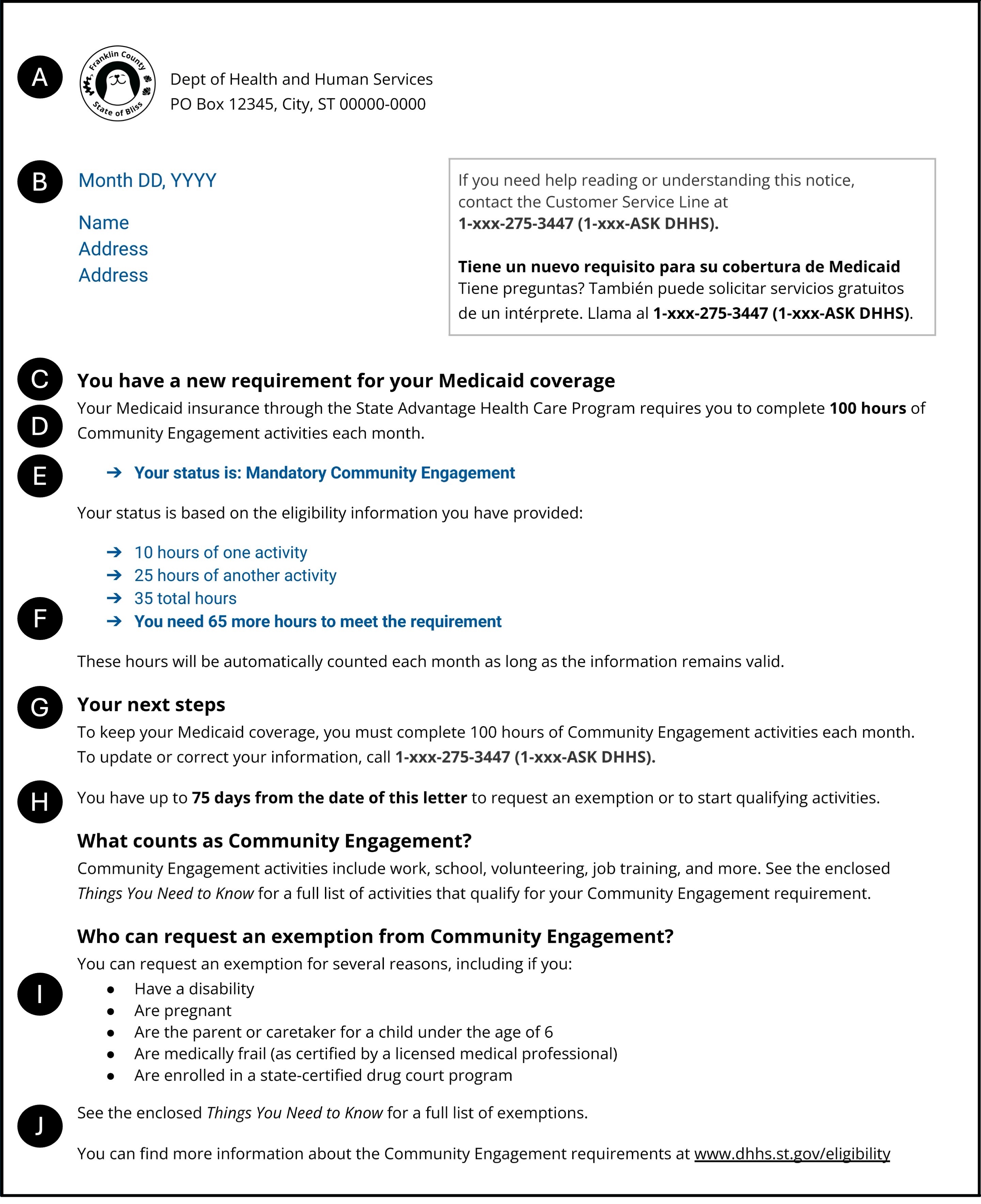

This is how we put it all together into a version of the New Hampshire letter that is clear, informative, and helpful.

Click on the image for a full-size version

A. Use a departmental seal or logo to make the letter look official, not just a computer printout.

B. Put information about support and how to contact the office at the top of the page.

C. Open the letter by identifying and explaining the problem. The tone should be friendly, but urgent.

D. Speak directly to the recipient, not to a general “people covered by Medicaid.”

E. Spell out status and information from the record clearly. Don’t abbreviate or use jargon.

F. Add it up – don’t make people do calculations.

G. Tell them how to take action if they see something wrong. Don’t wait until the end of the letter.

H. When possible, tell them the date of the deadline, not how many days. At a minimum, put the date somewhere clearly on the letter.

I. Use bullets for lists. It makes each item stand out, so the list is easier to scan.

J. Tell them how to find more information – including links to online sources.

Creating forms that inform is not that hard to do, but it does take some practice in plain language and in thinking about the recipient’s perspective. Too often, the focus of the letter is the regulation or program itself. Think about what each person getting this letter might need to know or do. For example, this letter is aimed at someone who is not meeting the new requirements. But what if they are already doing their 100 hours of work? Or, their record includes information that would give them an exemption?

Don’t write a one-size-fits-all letter and let everyone guess which parts apply to them or how to interpret jargony details. Instead, tailor the letter to different circumstances and let the computer insert the right message for each.

The bottom line is that how a policy is communicated makes a difference. Whether your vote is disqualified because you didn’t put a date on the envelope or you lose a critical benefit because you can’t fill out the forms, it’s a sign of a government that doesn’t work for the people it serves.