Communication and voter education is key to election innovation

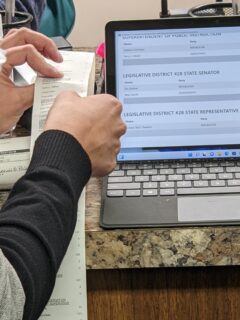

On November 8, 2022, voters in Franklin County, Idaho had the option to vote in a pilot of a new, innovative technology called ElectionGuard.

ElectionGuard is an open-source technology that lets voters confirm that their vote was counted and adds independent verification that the election results are correct. The idea was first introduced in 2006, but this was the first use in a General Election.

The project was a collaboration between technology researchers and developers, a voting system vendor, the state and local election offices, and the Center for Civic Design. We wanted to see whether end-to-end verifiability works in the real world of an election day polling place.

CCD’s work began several years ago, exploring ways to introduce a completely new technology to voters, poll wokers, and election officials. We were part of an amazing team of Microsoft, Hart InterCivic, Enhanced Voting, the MITRE Corporation, and Oxide Design. We developed the public-facing materials including handouts at the polling place, poll worker and administrator training, and general ‘explainers’.

We were also in Idaho on Election Day, observing the impact in the polling place and conducting exit interviews with 111 voters.

We wanted to understand voters’ experience of ElectionGuard – regardless of whether they took part in the pilot.

- Could they explain, in their own words, what ElectionGuard is?

- Did they value the opportunity to confirm that their ballot was counted?

- Did ElectionGuard add or detract from their voting confidence in the election results?

- Did the use of ElectionGuard disrupt the flow of voters through the polling place?

We joked that one of our metrics would be how many of the voter handouts ended up in the trash can at the door to the polling place. It was exciting to see that none did.

You can read a full report on the use of ElectionGuard and Hart InterCivic’s Verity precinct-scan voting system describing how the pilot was conducted and its results:

End-to-End Verifiability in Real-World Elections

We learned a lot about how to successfully introduce new technology to voters.

Simple, clear, minimal information focused on voter actions is better than technical explanations

We wanted voters to understand how this technology makes election results transparent and raised confidence in the election itself. But how much of the behind-the-scenes technical process did voters want to know?

We found that rather than trying to give voters a technical explanation of how ElecionGuard worked, providing them with clear information about what it achieves was much more effective.

Our first attempts tried to give a brief, clear explanation of the encryption technology and how it worked. In testing, it seemed that the more we wrote, the less people liked the explanation. Finally, we switched the approach to tell voters and poll workers what they would do and what ElectionGuard achieves. Testing shorter explainers that are focused on action was more effective.

In retrospect, this makes a lot of sense. We all use electricity every day but most of us don’t know how it works. The same goes for the internet, our smartphones and our cars.

Early on in our research, we found that rather than figure out how to explain the technology behind ElectionGuard, we needed to take a step back and ask what information did voters want to know.

It’s simple:

Voters want to know what problem ElectionGuard is solving and how it affects them, rather than how it works.

Apart from what information voters wanted, we needed to make sure voters received information about ElectionGuard at a time and in a format that made sense.

Breaking news! Voters do not like to be surprised on election day. A communication strategy helped set the stage for the pilot.

We worked on a communication strategy to create awareness of ElectionGuard before election day, including training materials for election administrators and poll workers and explainers and FAQs about ElectionGuard. A local newspaper covered ElectionGuard and voters received a letter about it before election day.

We think this awareness impacted voter reception of the pilot because by the time voters came across ElectionGuard at the polls, many had already heard about it. When we approached people about testing it out, more often than not, we were met with friendly acknowledgment and recognition as opposed to confusion.

Voters will embrace new technology (if prepared for it)

Of all the people we spoke with on election day, almost no one responded negatively to the pilot. On the contrary, most people were proud their county was chosen for the pilot and many expressed the importance of a verification system like ElectionGuard. “It’s an honor for our district to be chosen to test,” and “It’s great that they’re trying it out in a rural county,” are two statements we heard from voters and poll workers about the pilot.

We were also encouraged to discover that the people who opted out of participating still understood the purpose of ElectionGuard. This told us we’d communicated the project correctly, and that voters were not opting out because they didn’t understand what was being asked. The ones who chose not to participate said they were generally comfortable using new technology but some said they were “old school” and less eager for change.

The positive reception is encouraging news for pilot programs within elections in general, Sean, a designer and researcher at CCD, shared. It means there is potential for future pilots and experiments in election technology.

“I was expecting to see a lot of skepticism about Microsoft being here, and about using computers and cryptography and we didn’t hear that,” Sean added. “It was not nearly as controversial or divisive as I maybe would have expected.”

About the work

This project was led by Alex Haraseyko, Isabelle Yisak, Sean Isamu Johnson, and Whitney Quesenbery.

We were proud to partner with Microsoft, Hart Intercivic, MITRE, Enhanced Voting, InfernoRed Technology, and Oxide Design.

This was originally published in our Civic Designing newsletter. Subscribe on Mailchimp to get election design tips delivered to your mailbox.