Solving the double vote problem in New York State through design

In 2010, New Yorkers voted on paper ballots for the first time, giving up over 50 years of voting on mechanical “lever” machines. The lever machines were big, heavy and clunky. They had a few flaws: when they failed, votes were simply lost forever. They were hard to use if you were short, tall, didn’t read well, or couldn’t see.

But they did have one big advantage: they did not allow you to make more choices than allowed in any contest. This kind of error is called an “overvote” – and means that your vote doesn’t count.

Paper ballots have a lot of advantages: voters can review their choices, they can be audited, and close elections can be recounted. Unfortunately, they also make it easy for voters to make mistakes like overvoting. That’s why it’s so important that the ballot scanners have messages that actually help voters understand how their ballots will be counted.

New York has another unique feature. One candidate can appear on more than one party line. For example, Andrew Cuomo, the current Governor, ran as a candidate for the Democratic, Liberal, and Working Families parties.

What happens if someone votes for one candidate under more than one party (that’s called a double vote)? It seems clear that they want to vote for that candidate, so New York State wisely decided that the vote should count.

But then, New York decided that the “credit” for the vote would go to just one of the parties – the largest one. They also decided not to tell the voter: the ballot scanners would just make the decision for them. Naturally, the smaller parties objected—and (with the Brennan Center for Justice) sued the New York State Board of Elections.

The first question was how bad this problem would actually be. To help answer it, in October 2010, a dozen UX professionals ran a flash usability test across New York City. They went to 5 locations (in Manhattan, Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn) and asked people to try marking their ballot. By the end of the day, they had collected over 200 ballots. That’s a lot of data. The ballots had both overvotes and double votes. It’s also a lot of opportunities to observe how people mark their ballots. They learned that even in this small convenience sample of voters, some did care about which party they voted for. They also learned that the ballot design in New York City is a little bit confusing.

Fast forward to September 2011, and the outcome of the lawsuit. The Board of Elections agreed:

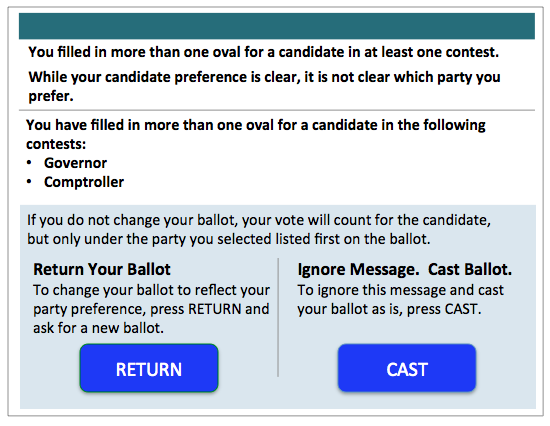

1. To set up the ballot scanners to alert voters when they have double votes, to explain the consequences, and to provide voters with a meaningful opportunity to change their ballots. Here’s a sample of what the message will look like.

Sample message for overvotes includes an explanation of the problem, the contests affected, and options for what to do next.

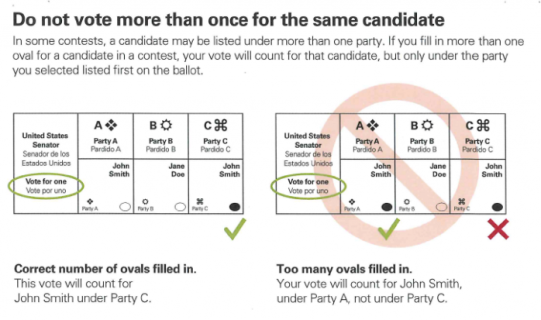

2. To post a notice in all the polling places that explains double voting and tells voters how to avoid it. The notice will be customized for the ballot design in each county. It will look something like this:

New educational material for voters in New York State to prevent double voting

3. To train poll workers, with a consistent procedure across the whole state, to help voters who try to cast a ballot with a double vote, so that voters can make changes if they want to.

4. To report the number of double votes that are recorded, despite these efforts, and make this report available to the public.

It’s a great outcome. It’s an example of a good collaboration between UX professionals interested in improving our community and civic life and civil rights organizations like the Brennan Center. I’m really proud to have been part of this work. We are also working with the Brennan Center to update New York’s election laws and improve ballot design and instructions.

Even as we celebrate, it’s hard not to wonder why it takes a year-long lawsuit to get one small thing changed. There is so much that needs improvement. Better user experience research, better ballot design, scanner messages, design and plain language of all voter information and poll worker materials, and—above all—usability testing before an election could do so much. Isn’t it time that we changed the process of how elections are designed?

Want to help?

- Let your local, state, and federal officials know that you care about the UX of elections.

- As of November 2015, there is a change.org petition from Vote Better NY to support better ballots

- Sign up to be part of any future election usability projects.

- Be part of your local elections as a voter or a poll worker.

- Get in touch with your local elections officials and offer your help as a UX designer.

Credits: Larry Norden and John Travis at the Brennan Center did a lot of the work to organize the flash usability test. They printed the sample ballots and arranged for locations for the tests. Chris Fahey, Jessica Friedman, Whitney Hess, Jonathan Knoll, Michele Marut, Paul Erb, Greg Palmer, Ashley Pearlman, Mary Quant, Aaron Schwartz, and Whitney Quesenbery ran the sessions, along with interns from the Brennan Center.

Fine print: The lawsuit was filed in United States District Court, Southern District of New York. It was settled with a consent decree among all the parties, signed on September 8, 2011. The lawsuit challenged the New York Election Law §9-112(4) and the corresponding regulation, 9 N.Y.C.R.R.§6210.1(a)(7)