The epic journey of American voters

In most of the U.S., getting to vote is not easy. Sure, it’s pretty straightforward to determine who is eligible: You must be a citizen of the United States and at least 18-years-old to cast a ballot in federal elections. But after that, there’s very little that is straightforward about U.S. elections.

In hearing from hundreds of voters through several research projects over the last 5 years at the Center for Civic Design, we have learned a lot about the path to Election Day.

During the 2012 presidential election we looked at 145 county election web sites to see what information was most prominent on them, and then asked 40 voters to try to find answers to their questions about the election on their local election department websites. In 2013 through 2015, we interviewed more than 100 first-time and low-propensity voters to understand their information needs. Then, leading up to the 2016 presidential election, we followed 50 voters through their processes for getting informed about that election for about 8 weeks.

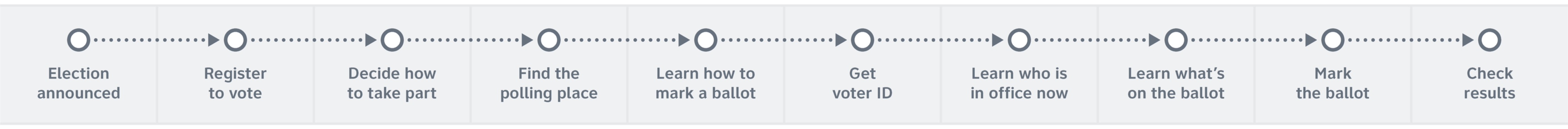

The expected path

The expected path is built on a chronological process.

When we look at election websites it’s clear that there is an expected, chronological process:

You register to vote, and then figure out your options for taking part, then do your homework about who the candidates are and what’s on the ballot. Then you vote.

But voters don’t think the same way that election officials do. Instead of starting at the beginning, they start with the question, What’s on the ballot?

We think that what they’re really asking is something like, What is important enough about this election for me to invest time and energy? What will happen in this election that will affect me and people I’m close to so much that I should do whatever it takes to vote? They’re asking, Is it worth the effort.

The way we talk about the process leaves a lot out. Voting isn’t as easy as 1, 2, 3. Third, there are more steps than most privileged voters think about. At each of those steps, voters weigh tradeoffs.

In other words, they are weighing the benefits of taking part and the potential value of outcomes to them against the costs of time, money, attention, decision-making, and relative hassle. When information is hard to find, or there are hurdles to taking action, the cumulative effect of the barriers can outweigh the initial desire to vote.

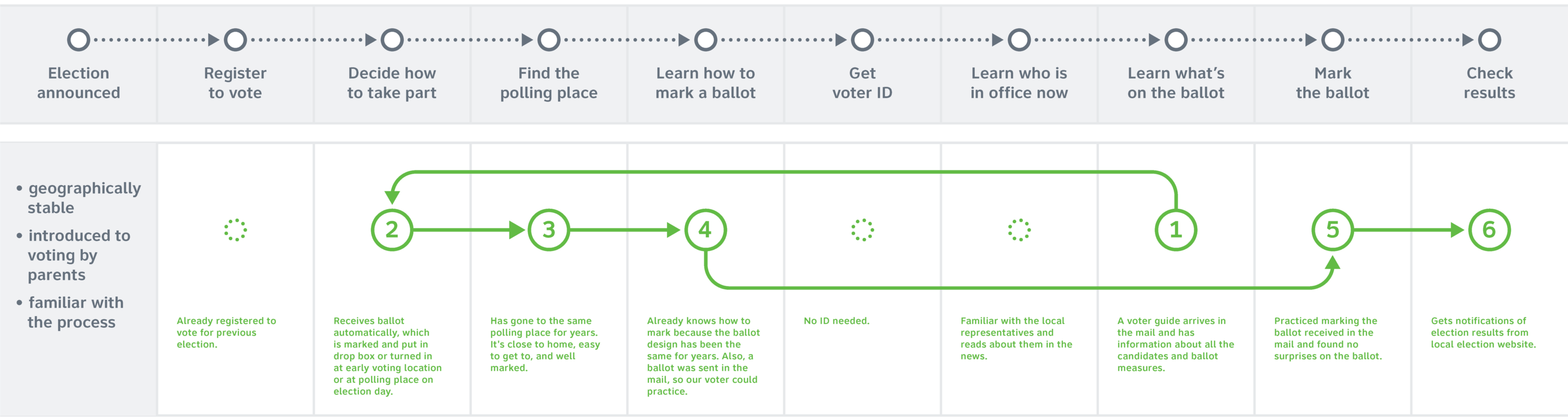

The happy path

The more frequently you vote, the less intimidating the process is. But still, your happy path does not match the expected path that election officials lay out as a chronological process. Your process looks more like this:

Even the path of a privileged voter doesn’t follow the expected process.

- You hear about an election coming up. You’re already wondering what’s on the ballot, and if you live in the 9% of jurisdictions that send information directly to voters ahead of elections, a voter guide with a sample ballot in it arrives in your mailbox.

- You have habits. Maybe you vote by mail so your ballot comes to you. Or you really like going to your neighborhood polling place. So this decision isn’t so hard.

- Because you vote regularly, you know where your polling place is.

- You don’t need to learn how to mark your ballot. You’ve done it plenty of times.

- You’re prepared. You may even have marked a vote-by-mail ballot, or you’ve made a list of how you want to vote. Marking your ballot is easy.

- Because you’re curious and invested in the outcomes, you want to know the results. Maybe you checked the local paper, or maybe you went to your county election website.

This path is pretty much the ideal. The decisions to be made are options to choose from, none of which present much friction.

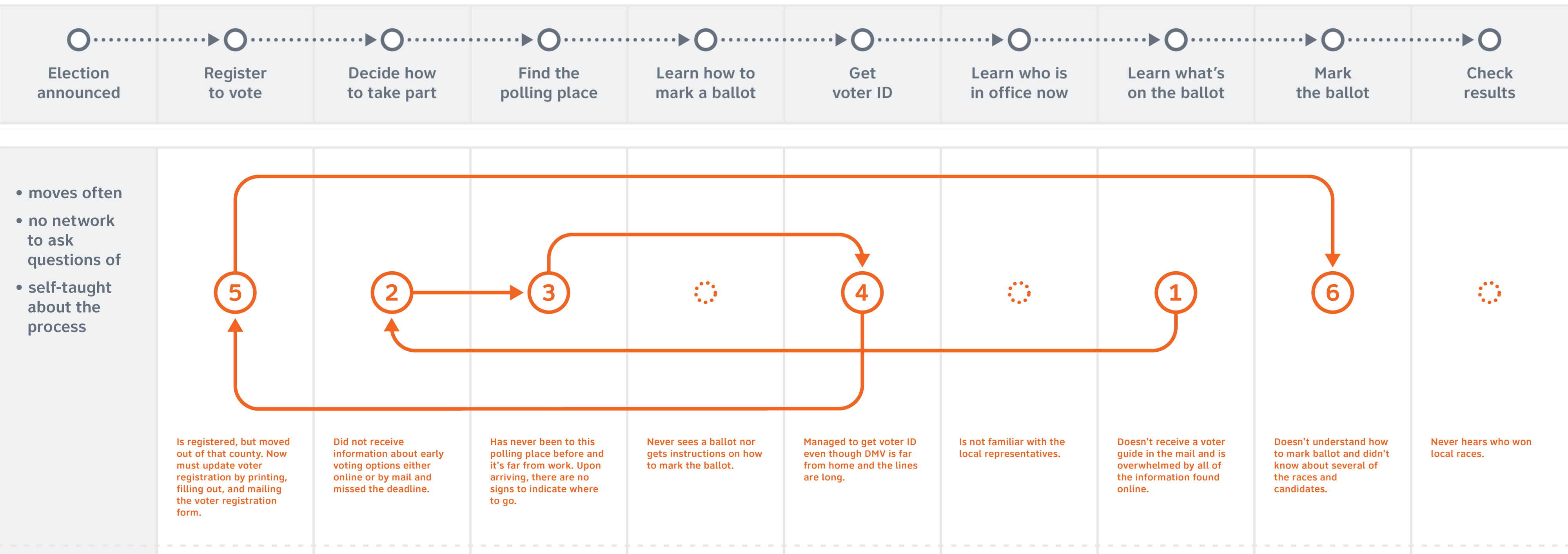

The burdened path of challenges and friction

If you are someone who has moved at the wrong time, or moves often, haven’t voted before or it’s been a long time, and you aren’t connected to someone who can guide, influence, and teach you about voting, your path will be far rougher.

The obstacles you encounter without basic civic literacy and experience can be huge and costly. The order of steps you go through will be similar to the happy path. But there are far more things to learn and to make decisions about. The burden accumulates across the experience, too. Even as you overcome challenges early in the process, the frustration that accompanies each victory stays and piles up. Even for someone who is tenacious, the burdened voter must have incredible grit and motivation to make it through the many hurdles.

Voters in our studies met hurdles in learning about

- Dates, times, and deadlines coming up – or that they may have already missed

- Information about what’s on the ballot

- When and where they can vote

- Where they can get information in their language materials or how to get voter ID

Even after gathering all the information, they had to juggle the logistics of voting against daily routines and the demands of work and family.

So, if you’re the burdened voter, your path looks more like this one:

The voter journey: The burdened path

You still start by trying to learn what’s on the ballot, and weighing whether it is worth taking part.

But instead of an easy, straightforward process, you have to struggle to understand what you have to do and how and where to take each step. The questions cascade at each step. What are your options for voting? Do you have to vote at the polls on Election Day? How do you get an ID to vote? Do you even need one?

When you finally get to the polling place, there are more surprises and more questions. You knew you were voting for President, but what are all these other things on the ballot? Can you find out about them on your phone while you’re in the voting booth? Can you ask someone about how to mark the ballot? What if you make a mistake? What if you don’t vote on all of the contests? Will your ballot still be counted?

It’s all pretty stressful, scary, and overwhelming. After this experience, are you more likely to vote in the next election because you have overcome? Or face the next election with dread? Even though you manage to cast a ballot in this election, the overall experience has not been the kind that inspires someone to love voting.

If there is apathy, it comes from the system not the voter

Most of us think about “voter apathy” as something that applies to other people who aren’t interested or concerned about civic life — or they believe that their votes won’t matter.

Our research shows that very few people really don’t care. Deep down, almost everyone does care about voting, and they feel shame for not doing it.

The real problem is that voting in America is just hard.

The burdens are costly and the frustration of overcoming them is cumulative. As people weigh the tradeoffs between taking part in a process that is difficult against a possible but unknowable future that they might influence by voting — it’s not that they don’t care. It’s that they are making rational decisions that they may not even be aware of at every step about what they care about right now.

A longer version of this article is available on medium.com/civicdesigning

Resources

The Voter Journey poster (pdf)

Text in the Voter Journey poster (xlsx)

Research report: Usability of County Election Websites

Research report: Informed Voters from Start to Finish: Voter research and usability testing

Best Practices Manual for Official Voter Information Guides

2 Comments

-

The epic journey of American voters | Dana Chisnell/Center for civic design | Verified Voting

-