New York should have piloted their new voting system

New York should have piloted their new voting system

It would have been so easy. So inexpensive. So quiet. Run a mock election, learn some lessons, talk with election officials from other places about how they transitioned from one voting system to another. As Larry Norden of the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU remarked on WNYC on November 2, “49 other states have done this before us.” But the New York Board of Elections did none of this, and the changing of voting systems seemed to be on the legislative agenda not at all. Instead, the Board and all the counties in New York did the equivalent of live usability testing in the primary in September and November.

New York has known for several years that the state would have to ditch the generations-old mechanical lever machines for new voting systems. There was plenty of time to prepare for this historic transition. And there were plenty of people around who could have helped. Key people offered. And, there are plenty of resources the state board of elections could have tapped. There are evidence-based federal guidelines for election design. There are thousands of experts on changing voting systems across the US. Oh, and there are dozens of local design experts who the state and city boards of elections could have called on.

But none of that happened. Why? For the purposes of narrowing the discussion, let’s just focus on ballot design.

Why the New York ballot is a disaster

While on its face, ballot design seems like a simple thing to do well, it is actually a complex mix of constraints and interactions. There’s the fact that the software for creating ballots is usually so difficult to use that many jurisdictions outsource it back to the voting system manufacturer. Next, most people who design ballots are not trained in design, they’re trained to be election administrators. Part of that is controlling costs. Local election officials are smart, well intentioned people. But if it comes to deciding between expanding a ballot to two cards to make it easier to read and use, or keeping everything on one card because it saves the county money on printing (and mailing) by making the font smaller and the spacing tighter, many election officials are going to go with smaller, tighter type.

It would be completely unfair to blame the design of the New York ballot on local elections officials, though. In fact, a lot of ballot design is out of control of the local elections official. The responsibility here lies with regulations, history, and bureaucracy. Typefaces and wording for instructions are often specified in election regulations. Community history and norms make up traditions that are embedded in local culture. And, many ballot design decisions are made at the state level, usually without consideration of usability data. Let’s talk about just those factors for a moment.

Some design problems are embedded in legislation

According to New York election law, the ballot must be “full face”. That means that everything to be voted on must appear on one side of the ballot. (The November ballot actually violated this; the ballot questions were on the back of the candidate contests.) There’s some logic to this, I suppose; New Yorkers have been voting on lever machines for a long time. A major change in the look of the ballot might throw voters off completely. But I doubt that.

In addition, the instructions are legislated in the election code. This is very common across the US. Some states are more flexible on this than others, even though the wording is legislated. New York codified its instructions without regard to the final ballot design. And the final ballot design didn’t take into account what the legislated ballot instructions must say. Instruction (2) reads: “To vote for a candidate whose name is printed on this ballot fill in the oval above or next to the name of the candidate.” But the bubbles for candidates appear below the names.

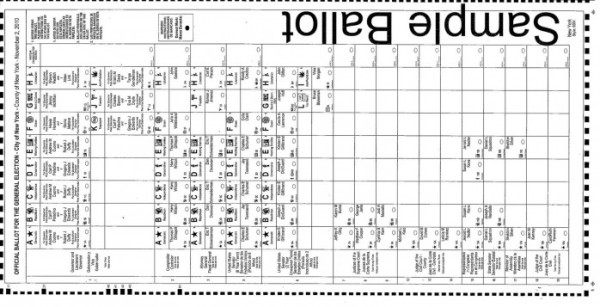

New York City November 2010 sample ballot

Tradition also influences ballot design

New York uses fusion voting. That means that although one party nominated a candidate, other parties can endorse a candidate as theirs. For example, on the 2010 midterm ballot, Andrew Cuomo appears as the Democratic candidate for governor, but also as the nominee of the Independence party and Working Families party. If you really want Cuomo to be governor, might you mark him in all three places? That’s called a double vote. But only one counts.

Mechanical lever machines prevent double voting. Officials doubted that voters would make this mistake on paper ballots, but there’s nothing to prevent it happening. In fact in a large usability test on October 9, 2010 sponsored by UPA, AIGA’s Design for Democracy project, and the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU, we found that double voting was not fiction. What about taking away fusion voting to prevent these kinds of voter errors? Fusion voting is legislated, but it is also deeply embedded tradition. Removing the option probably would have devastating effects on smaller but highly active political parties.

Bureaucracy gets in the way

The usability test on October 9 was conducted by a group of concerned volunteers, for free. Why didn’t the New York Board of Elections do a test? This is a mystery. The Brennan Center and UPA offered months ago, but the BOE declined, saying that they had spent all the money they were going to spend on the new systems. And, though the board had been warned about likely problems, the state BOE entered the state primary election in September 2010 in denial. That Election Day clearly showed the predictions of problems to be true, and fusion voting wasn’t even part of the ballot in the primary. In response to appeals for simple, inexpensive remedies, the Board said it was too late to make changes that they said required the voting system to be recertified and too late to make other changes because of how close the November federal election was.

What the design community can do about it

One of the wonderful things about working in election design is how easy it is to affect immediate, positive change. There is a woeful lack of involvement from the design community in election UX. Your country, your state, your town all need you. Here’s what to do:

Meet your local elections officials

Mayor Bloomberg and Governor Cuomo are not going to come to you. You have to go to them. Let yourself be known. If you live outside New York County, get yourself to the county election department and introduce yourself. Ask for time with the election director. Ask questions, and then listen. Make yourself available to them without expectation of monetary profit. (There’s very little funding for design and testing in local governments right now.)

Do civic duty

Sure, you vote in every election, but have you ever worked an election? There is so much to learn by being a poll worker about how election administration works and how voters vote. Immersion holds many lessons.

In most communities, there are also citizen advisory committees that work on voter outreach and voter education. When I lived in San Francisco, I was on a committee that wrote summary digests of ballot measures for the Voter Information Pamphlet.

Yes, these things can take time away from work. But what’s more important: a little less income, or doing your part for world peace?

Read the guidelines

There’s a lot of guidance on how to design for elections. You might start with Marcia Lausen’s book, Design for Democracy. It gives a high-level very Design view of ballot design. The Brennan Center’s report, Better Ballots gives 13 case studies that show that specific ballot design elements may have affected election outcomes. AIGA’s Design for Democracy project has compiled a very good collection of tools and resources. Read through what’s there.

Get to know the LEO Usability Testing kit

The Usability Professionals’ Association realized years ago that there weren’t enough usability specialists to test all the ballots out there. What to do? Give local election officials (LEOs) tools for doing testing on their own. The LEO Usability Testing Kit is in wide use in many counties across the US, but it’s also a great tool for volunteers to use to run mock election usability tests.

Make election UX a topic at local community meetings

After you get your feet wet in the election UX world, tell the story to other designers. Have them vote a badly designed ballot and talk about that experience. Encourage them to get involved.

Where the New York ballot is going from here

After a little media attention for sloppy design that might have prevented voters from voting as they intended, counties and states usually get the message. Florida is no longer the poster child for messy elections, Ohio inherited that honor for the 2008 presidential election. Now, its new sibling New York is competing strongly to outdo Ohio. Let’s hope that New York wakes up and reforms its election board and administration.

In the meantime, the New York State Inspector General conducted an investigation of the reported issues with the September 2010 primary. As Larry Norden of the Brennan Center for Justice wrote, “It is remarkably well-written, and it is sinister, sad and comical all at once.”

After the primary, the Brennan Center filed a law suit against the New York State Board of Elections, “over a discriminatory New York State policy for counting political party votes under a procedure known as ‘double voting.’ … The policy unfairly penalizes both the voters and the minor parties they support.” You can read a bit about the suit on the Brennan Center web site.