Innovations in Accessible Elections – Final Report

Download the report as a PDF file

In 2011, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) received a grant from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) to help make elections more accessible for people with disabilities. ITIF worked with research teams across the country to assess the current state of accessibility in elections, identify where technology has not lived up to its potential, and build innovative solutions to meet voters’ needs.

We reviewed every part of the election process, from registering to vote to casting a ballot. Our goal was to discover innovative ideas for elections that are:

- Universal, so everyone can use the same technology

- Flexible, allowing for differences in voter needs, election procedures, and state laws

- Robust, based on best practices and able to keep up with technological change

In addition to launching focused research projects to make improvements in voting system hardware, user interfaces, ballot designs, voter education materials, and poll worker training, we also created an open, collaborative process that would allow anyone to contribute ideas. In the end, we designed, built, and tested a number of innovative solutions to help bring us closer to the day when all citizens, with or without a disability, can vote privately, securely, and independently. This report catalogs some of these achievements.

Introduction

Voting is an important activity for citizens in any democracy, but when elections are not accessible, as many as 1 in 5 potential voters—47 million individuals in the United States—face barriers to voting.[1] Voters may have a variety of disabilities, including sensory disabilities (blindness, low vision, deafness, and hearing loss), cognitive and intellectual disabilities, mobility and dexterity disabilities, and communication and language-related disabilities. Although voting accessibility has improved since the Help America Vote Act (HAVA), people with disabilities register and vote at lower rates than other Americans and face unique challenges at the polls.[2]

One reason that elections are not as accessible as they could be is that people with disabilities are sometimes ignored in the design of new technology and services, with accessibility added as an afterthought. A better approach is to design for universal access. Universal design is the principle that technology and services should be built so that they can be used by everyone, to the greatest extent possible. One approach to universal design is to focus not on the “average” user, but instead on those with the most extreme needs. This approach allows designers to see problems from a perspective that encourages new ways of thinking.

Using universal design to improve elections can help eliminate existing barriers for people with disabilities, as well as make the voting process better for everyone.

Elections Today

Although the gap in participation between voters with and without disabilities has narrowed, people with disabilities are still less likely to vote than people without disabilities. In particular, individuals with a cognitive difficulty, a self-care difficulty, or an independent-living difficulty, vote at significantly lower rates than individuals with no disability. These individuals may have trouble leaving their homes or navigating crowded, noisy environments, so efforts designed to make voting machines and polling places physically more accessible may not address their primary needs.

Some states have made changes to election processes to make them more convenient for everyone, such as allowing “no-excuse” absentee voting (i.e., any voter can vote absentee) and creating a permanent absentee voting list (i.e., voters can sign up to receive automatically an absentee ballot for all future elections). While people with disabilities are more likely to vote in states that have made these changes, these reforms have not been adopted everywhere.

What problems do voters with disabilities experience?

Voters with disabilities share a set of experiences that are different from those of other voters. They are more likely to report problems registering to vote, to need help voting, or to face problems using the voting equipment.[3] These voters can feel excluded from elections when polling places, voting systems, or informational election materials are not accessible. Problematic social interaction at the polling place can also be an issue. Although many poll workers are friendly, willing, and courteous, too often they do not know how to set up and operate the accessible equipment and do not know how to recognize the needs of people with disabilities so they can provide effective assistance. As a result, voters with disabilities are less likely than others to vote in person (on Election Day or during early voting) than to vote by mail.

Barriers to Voting Experienced by People with Disabilities[4]

| Access to information about elections | Lack of accessible information about polling place locations Inconsistent or hard to find information about polling place accessibility Inaccessible sample ballots |

| Interactions in the polling place | Lack of knowledge about voting procedures and technologies Poll workers who do not recognize needs of people with disabilities Not enough poll workers to support voters throughout the voting process Lack of privacy and independence in voting |

| Physical environment of polling places | Polling place locations that are difficult to reach Inaccessible polling places with stairs, curbs, or other barriers Poor acoustics, making it difficult to communicate with poll workers |

| Poorly set up voting booths | Lack of seating while waiting or votingInsufficient leg room under tables for wheelchairs Voting systems at the wrong height or position |

| Inaccessible voting systems | Systems not set up for audio ballots or not functioning properly Difficult-to-use audio systems with poor quality audio Difficulties inserting or removing ballots Screen glare that makes the ballot hard to read |

What are the accessibility challenges with current voting systems?

There are a wide variety of voting systems intended for use by people with disabilities. Voters typically use a visual interface with a touch screen display. However, a voting system must include alternatives such as audio, tactile keys, and customizable displays to accommodate voters with a wide range of physical, sensory, cognitive, language, and literacy abilities. Even when these systems meet the basic requirements for accessibility in the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines—a set of specifications created by the Election Assistance Commission to create a baseline of performance for voting systems—many are not very usable for voters with disabilities. Problems with current voting systems include both how the system is deployed in the polling place and details of how voters interact with the system itself.

Examples of poor usability in voting systems

- Configuration processes for accessibility options that require assistance from poll workers

- Keypads with confusing or unusual layouts and keys that are hard to identify by feel

- Repetitive or confusing instructions, without context-sensitive help

- Difficult-to-use systems for entering write-in choices

- Poor design for privacy while using accessibility options

- Inconsistency between different voting systems adding to the learning curve

Election Innovations: Inclusive Design

Can individuals from a broad range of disciplines work together to build accessible solutions?

Too often attempts to reform elections exclude important voices. We showed how it is possible to design accessible solutions using input from individuals with a wide array of backgrounds and experiences. We organized a series of activities to explore current barriers and create new concepts for accessible elections that brought together collaborators from different backgrounds, including people with disabilities, advocates, election officials, technologists, and designers from many disciplines.

Open Innovation Challenge

ITIF partnered with OpenIDEO and Los Angeles County to sponsor an open, online innovation challenge around the question “How might we design an accessible election experience for everyone?” This challenge focused a global design community on accessible voting. Participants generated over 150 ideas in a structured process that allowed individuals from around the world to collaborate on concepts. Engaging designers from outside of the election world provided fresh perspectives on ways to eliminate barriers.

IMPACT: Los Angeles County, the largest jurisdiction in the country, is incorporating ideas from this project as it designs and develops a new voting system.

Participatory Design Workshops

ITIF partnered with the Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access to organize two workshops on designing accessible elections. Groups of election officials, advocates, and designers worked through exercises in design thinking that reviewed barriers and proposed ideas for solutions. Teams explored concepts using personas of voters with disabilities and principles of universal design. Facilitators created posters of the final concepts on ballot design, preparing to vote, voting at the polls, and voting remotely.

IMPACT: ITIF published a booklet for election officials illustrating fifty ideas created during the open innovation challenge and the participatory design workshops.

Election Innovations: Voting System Interaction

Can a joystick be a universal control?

Tactile controls, typically keypads that add hardware buttons to a voting system, are essential for making voting systems accessible for people who cannot use a touchscreen because of vision or dexterity disabilities. Current voting systems have a wide variety of solutions, but many are not very usable. For example, the buttons may be too difficult to feel or too hard to use, given the number of interactions on a typical ballot.

Many people with disabilities already use joysticks to control wheelchairs and other assistive technology. These can be engineered to meet the needs of people with little strength in their hands as well as those who can use a lot of force, but with little control of their movements. For other voters, joysticks are familiar as the controllers for games.

Custom engineering can make a joystick more suitable for use on voting systems:

- Movement of the joystick is possible in four directions: up and down to scroll through the options in a contest, left and right to move between contests

- Settings can adjust the effort needed to move the joystick, reduce unintended actions, and provide haptic feedback to the voters

- Buttons can be used to select an option, jump to the review screen, or go to help

- Mounting hardware can position the joystick to accommodate a range of postures

Usability testing found that a smart joystick may help individuals with a wide range of dexterity impairments, including muscular weakness, spasticity, and significant limitations of control, vote without significant discomfort and within a reasonable timeframe.

IMPACT: Los Angeles County is considering including a joystick as the tactile controller in its voting system redesign.

Can elderly voters use a tablet as a voting system?

In the 2012 election, the Denver Elections Department introduced a pilot program to allow adults with cognitive disabilities, and elderly voters living in long-term care facilities to mark their ballots using iPads brought by poll workers to their residences. Follow-up usability testing investigated whether voters who never may have used a tablet computer before could vote this way effectively.

Over three-quarters of the participants experienced some problems with gestures such as “tap”, “swipe”, and “pinch” because of common age-related disabilities such as mild tremors that affected the ability to tap accurately and dry skin that interfered with the use of the touch screen. Despite the problems, over 80% of the participants said they liked voting with the tablet and over 60% said they would opt to use the tablet in future elections.

IMPACT: The research found three easy ways to make a tablet-based voting system easier to use: 1) offer voters a stylus to use in lieu of a finger 2) use a stand to position the tablet to avoid glare on the screen, and 3) offer brief instructions and allow voters to practice using the basic gestures.

Can a custom-built case add accessibility features to a tablet?

The iPad and other tablet computers have been adopted widely for personal use by individuals with sensory, mobility, and cognitive impairments. The built-in accessibility options, such as gesture-based screen readers and screen magnification, are well-proven. In 2011, iPads were used by elderly and disabled voters in Oregon for a special primary election. However, for voters with a wide range of abilities, tablets should have easy-to-use tactile controls. Based on a winning concept in the OpenIDEO challenge, work began to design an iPad case with additional accessibility features, one that is self-contained and could be used to mark ballots anywhere, including outside traditional polling places.

The concept integrates a standard iPad with tactile switches. The design incorporates all the ballot-marking features needed for a self-contained voting system:

- Lightweight carrying case

- Built-in stand to adjust angle of the screen

- Integrated, retractable tactile keypad

- Jack for headsets or accessibility switch and volume controls in a convenient location

- Easy access for poll workers to home button, power button, and charging jack.

As one focus group participant with low vision said, “A beauty of using an iPad is that we’re not using a different device than sighted people.”

IMPACT: The design for the accessible iPad case is available online and can be built by election offices with access to a 3D printer.

Election Innovations: Ballot Design

Research on ballot design suggests that simple, clean interfaces both exemplify modern design and are more accessible than complex interactions or cluttered displays. Ballot information is also more effective when written in plain language, and concise instructions work best for people with low literacy. Election officials should ensure that any alternative language ballots also adhere to plain language guidelines.

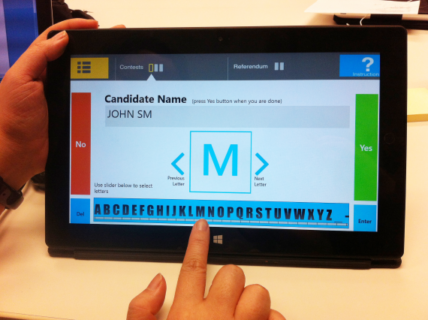

Can a voting system be designed to use only two buttons?

A prototype codenamed the “EZ Ballot” was designed for simple, linear navigation, using just two controls. It allows voters to make choices through a series of questions that can be answered by choosing “yes” or “no”. Once that design was perfected, a touch interface added direct access for non-linear navigation to candidates and contests. The EZ Ballot project showed that a multimodal interface can provide flexibility for voters.

IMPACT: Democracy Live, a company that makes voting systems, is working to incorporate EZ Ballot into its online ballot marking system.

Can a ballot be designed for use on any device?

A prototype codenamed the “Anywhere Ballot” found that rich information options on ballots distracted voters with low literacy and caused them to make more errors in marking their ballots. Instead, the most effective ballot design presents all the information and interaction in a clear reading order, at the place on the page or screen where the voter is already focused. Plain interaction means that it is easy for users to infer what to do from how the design looks and behaves. There is very little learning to do.

The Anywhere Ballot project showed that voters who are familiar with a gestural touch interface used those features easily on a ballot. Buttons with large touch areas helped voters who do not know how to use those features.

IMPACT: Los Angeles County is using the Anywhere Ballot as the basis of its ballot redesign.

Election Innovations: Voter Information

Election information can be complex. Voters not only must learn about the elections process and plan how they will vote (e.g., finding their polling place or choosing a voting method), but also read and understand details about the races, candidates, and ballot questions. Navigating this information is especially difficult for voters with cognitive disabilities that affect their ability to read, interpret, and remember written information.

Research on designing voter information for people with neurocognitive disabilities, including aphasia, Alzheimer’s disease, and traumatic brain injury, showed that clear, consistent writing and design is critical, just as it is for people with low literacy.

Strategies to make content accessible to people with cognitive and reading disabilities extend plain language and good information design to create usable, accessible voter information that benefits all voters.

| Strategy | Guidelines |

| Provide alternatives | Present content using multiple formats, such as combining printed text, images, and speech Present content using multiple phrasings, for example, presenting several synonyms for a word, or presenting both the positive and negative form of a statementInclude text-to-speech options, for voters who prefer (or need) to listen to information rather than read it |

| Keep it simple | Summarize key messages to reduce the amount of text and simplify complex passages Keep the navigation and design simple so it does not distract from the information Include a progress bar to show overall progress and identify gaps in non-linear reading |

| Help voters prepare | Provide a sample ballot that is an accurate version of the Election Day ballot, so voters can practice with it Allow users to annotate content, storing notes and selections between sessions so they can remember and track their progress Support social reading, allowing voters to discuss what they read with others or get help with the information |

IMPACT: Election officials can use these simple guidelines to make their voter education materials more accessible to people with cognitive disabilities.

Box: Lessons Learned

A few promising ideas did not work out when tested with voters. For example, a game-like interface for a voter guide was rejected in favor of a simpler design. Using an e-book format to summarize election information was not effective because this format is not widely used; voters preferred standard web formats, provided the pages are accessible. In a study of fonts on ballots, participants with and without dyslexia preferred the clear, readable Helvetica over specialized fonts for dyslexia.

Election Innovations: Working With Voters

Can election officials provide better services to long-term care facilities?

When voters cannot get to a polling place, programs can bring the election officials or poll workers to them. Pilot projects in two counties in California looked at the challenges in establishing and running election outreach in long-term care facilities. Facilities vary in the types of election services they provide to their residents. Some take an active role, others leave election activities to residents’ families, and some do not consider their residents capable of voting. Election offices can establish a good program by actively building relationships with key staff that manage access to the facilities and residents. These programs require dedicated staff to identify facilities, make appointments, and visit residents to register them to vote and then to assist them with voting.

Additional recommendations include:

- Start early—at least five months before an election—to allow time to schedule appointments

- Meet with facility directors early to explain the project, answer questions about election law and procedures, and provide training on voter registration to the facility staff

- Organize visits in advance, with group presentations on how to register and vote, and consider making video recordings that can be made available at the facility

- Schedule enough time with each resident, so that those who write slowly or need more time to understand ballot information are not rushed

- Have an audio version of the sample ballot available, especially for ballot measures

- Be ready to answer questions about who is eligible to vote and how to support those who need assistance

IMPACT: Election offices can learn from these pilot studies to get their own outreach programs off the ground.

Can better training improve poll worker interactions with voters?

Everyone who interacts with voters should be confident in their ability to help voters with disabilities in a respectful and appropriate way. This includes not only voters with visible disabilities, but those with hidden disabilities and those who may not consider themselves “disabled” or choose to seek help.

Using election scenarios, the Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access developed an online training course for poll workers. The training lets poll workers explore different ways to solve common problems in the polling place, with options that take election laws and practices into account. The course can be used for self-study or to supplement in-person training classes.

IMPACT: The online course “Assisting Voters with Different Needs” is available for the election community to use: http://www.accessiblevoting.gatech.edu

Moving Forward

While most elections are more accessible today than in years past, more progress is needed. State and local election officials should be encouraged to adopt best practices, such as online voter registration and no-excuse absentee voting, and to experiment with new programs, such as outreach to long-term care facilities, to better meet the needs of voters. Only through a process of continual improvement can the needs of all voters be met. The goal of every election official should be to make the next election better than the last.

Many of the improvements in elections will come from better technology. Advances in technology have created new opportunities for innovation in many public services, and voting is no exception. In particular, many of the voting systems adopted after the Help America Vote Act are coming to the end of their useful lifecycles and will soon need to be replaced, creating a new opportunity to invest in accessible voting technology. Voting system standards should be carefully crafted to ensure accessibility, while also encouraging innovation.

Unfortunately, there is no simple solution. Creating accessible elections will require sustained research and funding to continue designing new technologies and processes, evaluating them in the field, and training election official to use them. Ultimately, everyone involved in elections—from election officials to voting system designers to poll workers—must understand what voters with disabilities need to vote privately, independently, and securely, and how to do their part to make elections accessible.

IMPACT: The online course “Universal Design of the Voting Process” is available to help voting system designers and election officials learn how to make voting technology more accessible: http://www.accessiblevoting.gatech.edu

ITIF Accessible Voting Technology Initiative Collaborators

- Apps4Android – Voter Information Guide for an Android eReader

Steve Jacobs, Saurabh Gupta, Gaurant Kanvinde - Assistive Technology Partners – Assistive Technology in the Voting Process and Usability Assessment of the iPad for Ballot Marking

Greg McGrew - Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access (CATEA), Georgia Tech – Accessible Voting Workshops, Voting Experience of People with Disabilities, EZBallot, Training Course for Election Workers, Course on Universal Design for Voting System Designers

Jon Sanford, Karen Milchus, Frances Harris, Claudia Rebola, Tina Lee, Xiao Xiang, Elaine Liu, Ljilja Kascak, Caroline J. Bell, Hsiang-yu Yang - Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society (CITRIS) – Vote Your Mind (Voting Guide App for People with Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease)

Camille Crittenden, Faraz Farzin, Dan Gillette, Greg Niemeyer - Election Administration Research Center, University of California, Berkeley – Providing Election Services to People in Long-Term Care Facilities

Karin Mac Donald and Arshia Singh - Georgia Tech Research Institute – Web-Based Voting Application Studies and Accessible iPad Voting Case, Evaluation of Voting System Concepts for LA County VSAP, Investigation of Voting System Certification Procedures

Brad Fain, Carrie Bell, Andrew Baranak, Linda Harley, Keith Kline - Michigan State University – Voting with Joy (Smart joystick for accessible voting)

Sarah J. Swierenga, Stephen R. Blosser, Graham L. Pierce, Adi Mathew - University of Baltimore – Anywhere Ballot (Responsive, accessible ballot design for people with low literacy)

Kathryn Summers, Dana Chisnell, Drew Davies, Noel T. Alton, Megan McKeever. - University of Maryland Baltimore County – Voting Voice (Accessible voter’s guide for people with aphasia)

Shaun Kane - University of Utah and California Institute of Technology – Defining the Barriers to Political Participation

Thad E. Hall and R. Michael Alvarez - Center on Technology and Disabilities Studies, University of Washington – Current Voting Technology Analysis

Deb Cook and Mark Harniss

Acknowledgements

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation would like to thank all of the people who participated in our research. We would also like to thank OpenIDEO, the National Federation of the Blind, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the Election Assistance Commission for their generous contributions of time and ideas. Funding for this project was provided by a grant from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

[1] Matthew W. Brault, “Americans with Disabilities: 2010,” U.S. Census Bureau, July 2012, http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p70-131.pdf.

[2] Thad E. Hall and R. M. Alvarez “Defining the barriers to political participation for individuals with disabilities,” AVTI Working Paper #1, 2012, https://elections.itif.org/reports/AVTI-001-Hall-Alvarez-2012.pdf.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jon Sanford et al. “Understanding Voting Experiences of People with Disabilities”, AVTI Working Paper #5, 2013, https://elections.itif.org/reports/AVTI-003-Sanford-Milchus-Rebola-2012.pdf.

Back to the Accessible Voting Technology Initiative: https://civicdesign.org/?page_id=5720