Participating in Participatory Budgeting

We were pretty excited when Participatory Budgeting in New York City (PBNYC) asked Center for Civic Design to work with them on a project to understand the voter experience and how well their ballots worked for the diverse voters in New York in the 2016 elections. Of course, we said yes!

Participatory Budgeting allows community residents to have a direct voice in choosing how government funds are spent in their own neighborhood. Like a citizen initiative process, the ideas for projects come from people in the community. Like any election, there are polling places and ballots and poll workers. Voting happens over the course of a week in the culmination of a 6-month process in which the community develops the proposals.

The 2017 elections in New York City will take place from March 25 to April 2. Learn more at the New York City Council Participatory Budgeting pages.

PB polling places are like pop-ups, open at different places and times, to catch the most people and encourage participation across the diversity of each community. Polling places are run by each district City Council office, with both staff and volunteers from the community. This local management allows for flexibility, so the procedures and interaction with poll workers differed slightly across different districts.

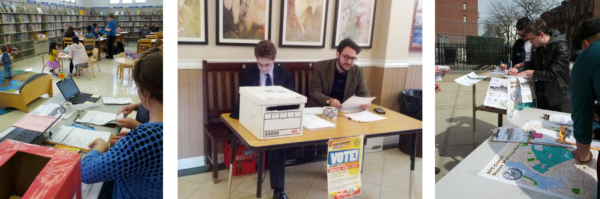

For this project, we went to locations in four boroughs in NYC to observe voting and interview people who had just voted. Over a period of three days, we interviewed and observed 73 people who voted at senior centers, community centers, public libraries and even street corner voting locations.

Most participatory voting locations are open for only a few hours at a time. The spaces can have an impromptu feel, different from a formal polling place with voting booths and ballot scanner. (Locations at a public library, community center, and street corner)

Digital ballot or paper ballot?

Our primary goal was to test the paper and digital ballots that had just been redesigned for 2016. Testing in real voting locations let us understand the setting and how Participatory Budgeting poll workers and outreach staff interact with voters, putting the act of voting in context.

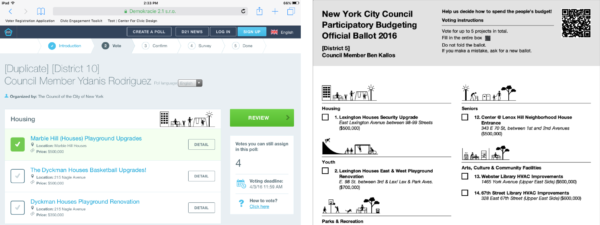

We wanted to know if all of the election design principles applied to this very different kind of election and how the paper and electronic ballots compared. Most of the voters 67 who we worked with used the paper ballot. The digital ballot was not available in all locations, so in addition to the 6 voters who used it, we also asked 19 other voters to test mock digital ballot voted on paper.

The digital ballot on a tablet and the paper ballots both included decorative illustrations to identify different types of projects.

Although most people liked the idea of a digital ballot, in reality paper almost always worked better in real polling places.

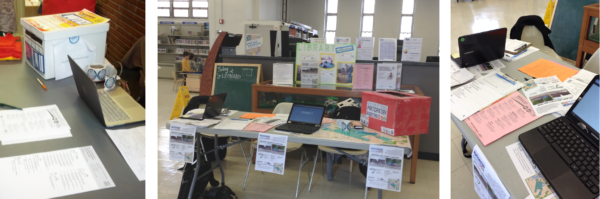

One reason for this is the nature of the polling places. At the registration tables themselves, there was not usually room for private voting. They were often set up at the entry to public venues like libraries or community centers. That’s a lot of foot traffic and distraction. The PB tables were also crowded with voting materials – sign-in sheet, voter oath, ballot, survey, voter guides, pamphlets and stickers.

In some, like some of the community centers we visited, poll workers handed out ballots to large numbers of people at a time, so they could vote before their lunch was served or another activity began. Many other voting locations did not have easy places to sit down comfortably to use the digital ballot. The computers served as electronic poll book, so voters had to stand and lean over the computer to mark their ballot.

Paper ballots also had a comfort factor attached to them – voters could take a ballot to a comfortable place to sit. We saw people fill out their ballots while sitting on stairs, at a desk in a library, on a bench, and other informal places. Digital ballots on tablets could give voters this same flexibility, but would not allow as many people to vote at one time.

Watching people mark a ballots also suggested that paper was easier. Even voters who liked the idea of using the digital ballot were sometimes confused about the digital voting process. They had trouble selecting their 5 projects, reviewing their choices, and confirming that the vote was cast. This made some voters feel less confident about the process. For example, if a voter selected too many choices, the error message was displayed at the top of the screen, far from the action of marking the ballot. Many never noticed them, and simply continued making more choices – none of which were recorded.

The paper ballots also had some basic design challenges. Voters put a cross or a check in the square marking boxes, and poll workers had to remind them to fill in the entire area so the ballots could be scanned correctly.

Making sure the ballots are easy and usable is critical for a project like Participatory Voting that aims to increase civic engagement. One poll worker told us “I want people to be empowered and fill in the boxes themselves. In a way I feel like I am taking it away from them and treating them like babies when I have to show them how to correctly fill in a box!”

Over the past year, the Participatory Budgeting team have been working on updating the designs, so watch for improvements in this year’s voting.

There were lots of materials on the tables: The ballot box, information about the projects, maps of the district, computers, poll books, and voter guides.

There were official information guides available, but few voters used them. Although some came to vote with specific projects in mind, most voters relied almost entirely on information and instructions present on the paper ballot itself to make their choices.

The digital ballot had some information available on the screen, but voters typically did not explore enough to find it. As with the paper ballot, they made their choices as they marked their ballot, often about the types of projects they wanted.

Voting in Participatory Budgeting is social

Using a paper ballot had benefits beyond the actual marking of the ballot. Filling a paper ballot was often a social interaction. It was a great activity for parents and children to do together, and voting became a teaching lesson, too. We saw children putting the ballot into the ballot box with great ceremony.

The polling places all had voter guides with information about the projects, but in several locations we saw posters and flyers that the advocates for different projects had created. Near one school, students handed out flyers asking people on the street to vote – and vote for the project in their school. Many walked on, but few could resist a middle-school student asking them to vote.

Fun fact

You don’t have to be 18 to vote in Participatory Budgeting. Many PB projects help build voting habits early, allowing people to vote at 14 years old, or even 11 or 12!

For most of our participants, finding a polling place was serendipity. They did not know much about Participatory Budgeting, but cared about the community enough to exercise their right to vote when presented with the opportunity. These voters were captured as they went about their day – an advantage to the highly visible, busy polling places.

Others liked having a way to be more involved in their community. As one voter told us, “When you are young [you don’t care] … Now that I’m older, I want to be more involved.” These involved voters participate to exercise their rights rather than push for a particular agenda.

A third type of voter knew about a project in advance and came to voter specifically to support that project. Many of these issue voters voted for just that project. Others looked for other similar projects or projects in their immediate neighborhood.

Poll workers play a crucial role in making voting smooth and efficient. As one bilingual poll worker told us, “People in public housing generally don’t trust the process, so my job is to make sure people participate here.” There were times, however, when the line between a poll worker and project advocate blurred. This made some voters uncomfortable as it felt that they were being asked to vote on a specific project, not to consider all of the options

Across the board, voting was an opportunity for people to be more civically engaged. Whether they knew about Participatory Budgeting in advance or not, they all liked the idea of having a voice in local decisions.

Participatory Budgeting is a highly collaborative and engaged process. Its planning, execution and implementation would not have been possible had not poll workers, school teachers, students, parents, grandparents, district staff, PBP staff and translators all come together to make it a reality. While testing ballots, we got to witness community engagement first hand through this project and came away with a renewed sense of appreciation for the power of engaged citizens.

About Participatory Budgeting

Participatory Budgeting allows community residents a direct voice in choosing the local projects that are funded by their local government. This novel idea of working directly with communities came about in 1989, in Porto Alegra, Brazil. Today, PB has spread to many other U.S. cities including Boston, San Francisco, Chicago, Long Beach, St. Louis, Greensboro, and New York City. The Participatory Budgeting Project works with local PB teams in 11 cities as they design processes that will allow residents to decide how to spend over $40 million in 2017.

Participatory Budgeting NY (New York City Council website

What is Participatory Budgeting

The Participatory Budgeting Project resources and toolkit

ParticipationLab Panel: Centering Accessibility in Creating and Choosing Tools

Webinar, December 2016

Why accessibility should be at the center of your work

Hadassah Damien, Participatory Budgeting (June 27, 2017)

1 Comment

-

A year-and-a-half in review: Center for Civic Design 2016-2017 | Center for civic design